Uses of Insulin

| Home | | Pharmacology |Chapter: Essential pharmacology : Insulin, Oral Hypoglycaemic Drugs and Glucagon

Diabetes Mellitus : The purpose of therapy in diabetes mellitus is to restore metabolism to normal, avoid symptoms due to hyperglycaemia and glucosuria, prevent shortterm complications (infection, ketoacidosis, etc.) and longterm sequelae (cardiovascular, retinal, neurological, renal, etc.)

USES OF

INSULIN

Diabetes Mellitus

The

purpose of therapy in diabetes mellitus is

to restore metabolism to normal, avoid symptoms due to hyperglycaemia and

glucosuria, prevent shortterm complications (infection, ketoacidosis, etc.) and

longterm sequelae (cardiovascular, retinal, neurological, renal, etc.)

Insulin is effective

in all forms of diabetes mellitus and is a must for type 1 cases, as well as

for post pancreatectomy diabetes and gestational diabetes. Many type 2 cases

can be controlled by diet, reduction in body weight and appropriate exercise.

Insulin is needed by such patients when:

· Not controlled by diet and exercise or when

these are not practicable.

· Primary or secondary failure of oral hypoglycaemics

or when these drugs are not tolerated.

· Under weight patients.

· Temporarily to tide over infections, trauma,

surgery, pregnancy. In the perioperative period and during labour, monitored

i.v. insulin infusion is preferable.

· Any complication of diabetes, e.g. ketoacidosis,

nonketotic hyperosmolar coma, gangrene of extremities.

When

instituted, insulin therapy is generally started with regular insulin given

s.c. before each major meal. The requirement is assessed by testing urine or

blood glucose levels (glucose oxidase based spot tests and glucometers are

available). Most type 1 patients require 0.4–0.8 U/kg/day. In type 2 patients,

insulin dose varies (0.2–1.6 U/ kg/day) with the severity of diabetes and body

weight: obese patients require proportionately higher doses due to relative

insulin resistance. A suitable regimen for each patient is then devised by

including modified insulin preparations.

Any

satisfactory regimen should provide basal control by inhibiting hepatic glucose

output, as well as supply extra amount to meet postprandial needs for disposal

of absorbed glucose and amino acids. Often mixtures of regular and

lente/isophane insulins are used. The total daily dose of a 30:70 mixture of

regular and NPH insulin is usually split into two (splitmixed regimen) and

injected s.c. before breakfast and before dinner. Several variables viz. site and depth of s.c. injection,

posture, regional muscular activity, injected volume, type of insulin can alter

the rate of absorption of s.c. injected insulin and can create mismatch between

the actual requirement (high after meals, low at night) and the attained insulin

levels.

Another preferred

regimen is to give a long-acting insulin (glargine) once daily either before

breakfast or before bedtime for basal coverage along with 2–3 mealtime injections

of a rapid acting preparation (insulin lispro or aspart). Such intensive

regimens have the objective of achieving round the clock euglycaemia. The large

multicentric diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT) among type 1

patients has established that intensive insulin therapy markedly reduces the

occurrence of primary diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy and slows

progression of these complications in those who already have them in comparison

to conventional regimens which attain only intermittent euglycaemia. Thus, the

risk of macrovascular disease appears to be related to the glycaemia control.

The UK prospective diabetes study (UK PDS, 1998) has extended these

observations to type 2 DM patients as well. Since the basis of pathological

changes in both type 1 and type 2 DM is accumulation of glycosylated proteins

and sorbitol in tissues as a result of exposure to high glucose concentrations,

tight glycaemia control can delay endorgan damage in all diabetic subjects.

However, regimens

attempting near normoglycaemia are associated with higher incidence of severe

hypoglycaemic episodes. Moreover, injected insulin fails to reproduce the

normal pattern of increased insulin secretion in response to each meal, and

liver is exposed to the same concentration of insulin as other tissues while

normally liver receives much higher concentration. As such, the overall

desirability and practicability of intensive insulin therapy has to be

determined in individual patients. Intensive insulin therapy is best avoided in

young children (risk of hypoglycaemic brain damage) and in the elderly (more

prone to hypoglycaemia and its serious consequences).

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (Diabetic Coma)

Ketoacidosis of

different grades generally occurs in insulin dependent diabetics. It is

infrequent in type 2 DM. The most common precipitating cause is infection;

others are trauma, stroke, pancreatitis, stressful conditions and inadequate

doses of insulin.

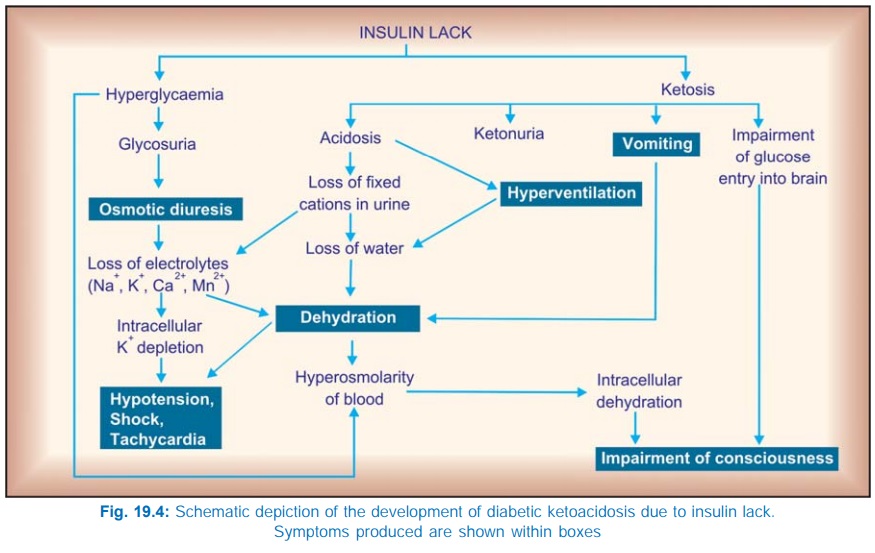

The development of cardinal

features of diabetic ketoacidosis is outlined in Fig. 19.4. Patients may

present with varying severity. Typically they are dehydrated, hyperventilating

and have impaired consciousness. The principles of treatment remain the same,

irrespective of severity, only the vigour with which therapy is instituted is

varied.

1. Insulin Regular insulin is

used to rapidly correct the metabolic

abnormalities. A bolus dose of 0.1–0.2 U/kg i.v. is followed by 0.1 U/kg/hr

infusion; the rate is doubled if no significant fall in blood glucose occurs in

2 hr. Fall in blood glucose level by 10% per hour can be considered adequate

response.

Usually, within 4–6

hours blood glucose reaches 300 mg/dl. Then the rate of infusion is reduced to

2–3 U/hr. This is maintained till the patient becomes fully conscious and routine

therapy with s.c. insulin is instituted.

2. Intravenous fluids It is vital to correct

dehydration. Normal saline is infused i.v., initially at the rate of 1 L/hr, reducing

progressively to 0.5 L/4 hours depending on the volume status. Once BP and heart

rate have stabilized and adequate renal perfusion is assured change over to ½N

saline. After the blood sugar has reached 300 mg/ dl, 5% glucose in ½N saline

is the most appropriate solution because blood glucose falls before ketones are

fully cleared from the circulation. Also glucose is needed to restore the

depleted hepatic glycogen.

3. KCl Though upto 400 mEq of K+ may be lost in urine during

ketoacidosis, serum K+ is usually normal due to exchange with intracellular stores.

When insulin therapy is instituted ketosis subsides and K+ is driven

intracellularly— dangerous hypokalemia can occur. After 4 hours

it

is appropriate to add 10–20 mEq/hr KCl to the i.v. fluid. Further rate of

infusion is guided by serum K+ measurements and ECG.

4. Sodium bicarbonate It is not routinely

needed. Acidosis subsides as

ketosis is controlled. However, if arterial blood pH is < 7.1, acidosis is

not corrected spontaneously or hyperventilation is exhausting, 50 mEq of sod.

bicarbonate is added to the i.v. fluid. Bicarbonate infusion is continued

slowly till blood pH rises above 7.2.

5. Phosphate When serum PO4 is in the lownormal range, 5–10 m mol/hr of

sod./pot. phosphate infusion is advocated. However, routine use of PO4

in all cases is still controversial.

6. Antibiotics and other supportive measures and treatment of precipitating cause must be instituted simultaneously.

Hyperosmolar (Nonketotic Hyperglycaemic) Coma

This usually occurs in

elderly type 2 cases. Its cause is

obscure, but appears to be precipitated by the same factors as ketoacidosis,

especially those resulting in dehydration. Uncontrolled glycosuria of DM

produces diuresis resulting in dehydration and haemoconcentration over several

days → urine output is

finally reduced and glucose accumulates in blood rapidly to > 800 mg/dl,

plasma osmolarity is > 350 mOsm/L → coma, and death can occur if not vigorously

treated.

The general principles

of treatment are the same as for ketoacidotic coma, except that faster fluid

replacement is to be instituted and alkali is usually not required. These

patients are prone to thrombosis (due to hyperviscosity and sluggish

circulation), prophylactic heparin therapy is recommended.

Despite intensive therapy,

mortality in hyperosmolar coma remains high. Treatment of precipitating factor

and associated illness is vital.