Hospital procurement and the application of EU legislation

| Home | | Hospital pharmacy |Chapter: Hospital pharmacy : Purchasing medicines

Overlaid on this background and history has been the impact of EU legislation. The UK is a member state of the EU and an aim of the EU is to create a single European market devoid of all trading restrictions and barriers a marketplace in which all businesses have an equal opportunity to compete.

Hospital procurement and the application of EU legislation

Background and requirements

Overlaid on this

background and history has been the impact of EU legislation. The UK is a

member state of the EU and an aim of the EU is to create a single European

market devoid of all trading restrictions and barriers a marketplace in which

all businesses have an equal opportunity to compete. The EU regulates and

monitors all large-scale public sector procurement through EU directives

covering the supply of goods, services and works. In the UK the directives

apply to all NHS contracting authorities and NHS trusts.

As a result of EU

membership, hospital procurement is subject to the directive within the Treaty

of Rome, including Article 12 (prohibition of discrimination on grounds of

nationality), Article 28 (free movement of goods within the EU) and Article 81

(prohibition of agreements that prevent, restrict or distort competition).

The main

requirements are:

· the advertisement of

large public contracts to a standard format in the supplement to the Official

Journal of the European Community (OJEC) so that suitable suppliers from all EU

and government procurement agreement countries have the opportunity to declare

their interest. Prescribed minimum periods for responses

· the use of technical

specifications which are non-discriminatory and which refer to EU or other

recognised international standards wherever possible

·

the use of objective criteria for selecting participants and

awarding contracts.

The directives only

apply where the value of the procurement exceeds a given threshold. This is

quoted in euros but, as a rule of thumb, means any contract with a value of

£100 000 is included. It should be noted that the figure is for the contract’s

lifetime, not an annual figure; thus, a contract for £30 000 per year for 3

years must go through this process.

Types of procedure

The regulations

recognise three contracting procedures open, restricted and negotiated. These

have slightly different requirements and advantages, and are summarised in Text

box 3.1.

Box 3.1 Types of contracting procedure

Open procedure

Available

in all circumstances and involves only a single stage. All offers received must

be considered, provided that candidates have passed any minimum short-listing

criteria. The open procedure can be conducted more quickly than the restricted

procedure but there is no possibility of limiting the number of bids received.

Restricted procedure

Available

in all circumstances but involves a two-stage procedure. From amongst the

candidates expressing interest (the first stage) it is possible to shortlist a

limited number from whom to invite offers (the second stage).

Negotiated procedure

The most flexible but the least transparent of the three procedures. It is used only in very limited circumstances (for example, where goods are needed urgently due to reasons that were unforeseeable by, and not attributable to, the buyer).

Offer evaluation

The directives

require that any contract must be awarded to the candidate who submits the lowest-priced

tender or the tender that is the most economically advantageous (buyers almost

invariably select the latter because it gives greater flexibility). The factors

that may be used to determine economic advantage include price, quality of

service and running costs: the chosen factors must be stated in the OJEC notice

or the contract documents.

Negotiation within the process

Where the open or

restricted procedures are being used, the rules forbid buyers to engage in

post-tender negotiations with candidates. These are defined as negotiations

with candidates on fundamental aspects of their bids, for ex-ample, price.

Discussions aimed as clarifying or supplementing the content of the bids are,

on the other hand, permitted, provided all candidates are treated equally.

Pre-tender discussions with potential suppliers, conducted on an equit-able

basis, are critical to designing contracts that will perform and deliver.

Types of contract

There are two types

of contract: the commitment contract and the framework contract. The commitment

contract commits a legal entity (such as an NHS trust) to purchase a defined

quantity of product at a defined price; the frame-work contract does not

guarantee to deliver commitment. Rather, based on estimated volumes it provides

(for example, on behalf of a group of hospitals represented as a purchasing

group) a framework against which purchase orders will be placed by hospitals

covered by the agreement. The framework agreement sets the terms and conditions

of the purchase by the hospital, including price/pricing schedules, with the

trust contract being formed when individual hospitals place their purchase

order.

Framework contracts

are normally used on behalf of purchasing groups in recognition that an agent

(such as the NHS CMU) or a hospital within the purchasing group cannot deliver

absolute commitment to volume on behalf of the group.

The strengths of the contracting process

It may appear

sometimes that the contracting process is cumbersome and bureaucratic. However,

recognition must be paid to its inherent strengths. These are that the process

is auditable, is legal (so minimising the risk of challenge, particularly when

the lowest bid is not accepted), provides a frame-work for equal treatment for

all bidders, establishes a clear trading basis between the NHS and its

suppliers (through standard terms and conditions) and provides a fair test of

value for money on behalf of the NHS.

The organisation of hospital contracts

Hospitals have

contracts at various levels: purchasing group, trust con-tracts, national. The

principles of purchasing group contracts are straight-forward. Hospitals

aggregate their purchasing power through their pharmacy purchasing groups and

the NHS CMU then competitively tenders, awards and manages the resulting

contracts, as an agent, on behalf of the groups. Each trust must nominate an

individual to represent the interests of its hospital managers, clinicians and

budget-holders (as well as its local relationships with primary care trusts) on

its purchasing group. The nominee’s roles include sharing information,

adjudicating contracts and participating in collective dialogue with the NHS

CMU buyer dedicated to work with the group.

The nominees use

their knowledge and experience that originate in man-aging medicines on a

day-to-day basis (particularly through formulary management systems that are

linked to drugs and therapeutic committees, and input into the prescribing

process) to direct the management of the contracts.

In England there are

six main purchasing groups operating on a geographical basis with some, varying

by main group, being divided into smaller groups. Each main group ‘owns’

contracts of between 1500 and 2000 lines, representing upward of 200 suppliers.

Whilst the contracts on behalf of these groups are framework contracts that do

not guarantee commitment, the ownership of the contracts (through the

participation of their member trusts) ensures that these contracts are highly

effective.

The framework

contracts on behalf of each purchasing group can vary in length. However,

typically they last for a maximum period of 2 years and include options to

extend for an additional 2 years.

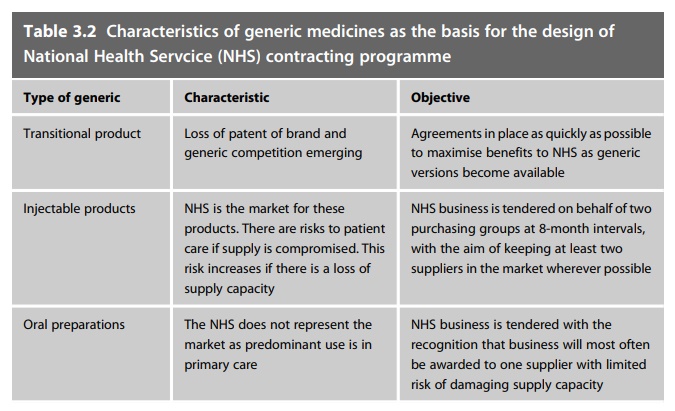

Following SCEP the

NHS now supports a nationally coordinated programme to contract for the supply

of its generic medicines. This is organised to reflect the characteristics of

the generics that are involved and is sum-marised in Table 3.2.

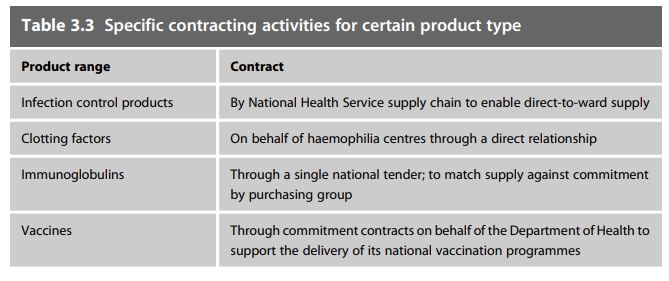

Alongside the

generic contracting programme there are tenders for branded medicines in the

same way but by local agreement with NHS CMU, making awards to reflect volume

discounts. This enables the NHS to benefit from competition between

therapeutically similar medicines where this exists. Some product ranges can be

separated out from the model to reflect the strategic development of their

procurement; these are shown in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Specific contracting activities for

certain product type

Product range : Contract

Infection control products : By

National Health Service supply chain to enable direct-to-ward supply

Clotting factors : On

behalf of haemophilia centres through a direct relationship

Immunoglobulins : Through

a single national tender; to match supply against commitment by purchasing

group

Vaccines : Through commitment

contracts on behalf of the Department of Health to support the delivery of its

national vaccination programmes

Pharmacy purchasing groups branded medicines and other activities

Contracts at

purchasing group level are more important when decisions around the clinical

choice of medicines can be influenced at a local level. Product ranges

contracted for at this level include: branded medicines; bulk fluids;

therapeutic tenders (where branded medicines have the same therapeutic outcome);

service contracts (for example home care, aseptic com-pounding and

overlabelling services).

Trust contracts

Some medicines will

still be contracted for at trust level, though the driver is to move as much

contracting to purchasing group and national level as possible, where

aggregation of usage improves purchasing power.

Systems and processes

Pharmacy specialists and working relationships with procurement

The technical and

procurement specialists within pharmacy strengthen the contracting

arrangements, especially where they are employed by a trust to support and work

with a purchasing group. Pharmacy quality control (QC) arrangements are

involved in assessing product quality as part of the tendering process, as well

as on a day-to-day basis (see Chapter 7 for further details on QC services).

Specialist

involvement, combined with day-to-day working relationships between trusts and

their buyer, minimises duplication of effort through shared access to central

contract management and associated procurement expertise.

NHS CMU management systems

NHS CMU manages the

contracting process using a system called Phacter. Phacter maintains a database

of all suppliers and product lines. It generates invitations to tender (through

an electronic format that suppliers access through an electronic portal Bravo)

and produces comparative evaluations to support contract adjudication before

finally generating award notices to suppliers and contract details to trusts

through a web-accessed catalogue.

NHS CMU also

collects, at each month end, in electronic format, hospital pharmacy purchasing

information through a system known as Pharmex. Pharmex data are used to scope

NHS secondary care business for tender. They also provide individual trusts and

NHS CMU with measures reporting the performance of the contracting

arrangements.

Through a third

system, PharmaQC, NHS CMU collects and stores product images and supply chain

information from suppliers. The QC pharmacists access this system to record

their product assessments. Available at adjudication, via the system, this

information ensures that QC product quality and risk assessments are reflected

when contracts are awarded.

Meeting structures

The totality of the

contracting arrangements is underpinned through meeting arrangements and

communication structures. The pharmacy purchasing groups, elected chairs and

their buyers meet regularly to share information, adjudicate contracts and

monitor performance. At the national level the Pharmaceutical Market Support

Group (PMSG), consisting primarily of the specialist procurement pharmacists

and NHS CMU specialists, brings pharmaceutical expertise around a focus of

contract management, making sure that security of supply is placed above

savings. PMSG is supported by various working groups dedicated to specific

workstreams. It reports to the National Pharmaceutical Supply Group (NPSG).

NPSG membership consists of NHS trust chief pharmacists and PCT advisors. Its

role is to provide advice to NHS CMU to ensure that it manages and develops its

service in line with NHS requirements. Lastly, the chairs of both NPSG and PMSG

attend regular meetings with the Department of Health chief pharmacist, the NHS

CMU general manager, amongst others, to ensure that there is an exchange of

information with Department of Health col-leagues working at policy level.

Recent changes

All of the following

changes will have long-term impact.

Home care

The growth in the

supply of medicines to patients at home, either as compo-nents of packages of

care or just simply as a route of supply, has been dramatic. Home care now

represents a major part of NHS business. The NHS focus lies with the National

Homecare Committee.

Other service contracts

Stimulated by

policy, by National Patient Safety Agency guidance and increasing demands on

its finite capacity, the NHS is increasingly outsourcing other services such as

outpatient dispensing, the provision of aseptically prepared products and

‘specials’ in addition to home care. Over time these changes will have an

impact on contracting and procurement.

Payment by results and NICE

As described in

Chapter 1, for England, payment by results has started to change the dynamics

within the market for those high-cost medicines that are not included in the

payment by results tariff (and particularly those approved by the National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): see Chapter 11). The PPRS

2009 allows pharmaceutical companies to pro-pose patient schemes to improve the

cost-effectiveness (cost per quality-adjusted life-year) of medicines. If NICE

approves or partially recommends the medicine, these schemes become operational

in order to achieve the cost-effectiveness approved by NICE. Types of scheme

include free stock, rebates, straight discounts (applied to invoices at order

point) and dose caps. Whilst providing access via the NHS to a wider range of

medicines at cost-effective rates, these schemes have added a not

inconsiderable burden to NHS medicines purchasing teams.

Security of supply

Globalisation within

the pharmaceutical industry, associated with company mergers, rationalisation

of manufacturing capacity, product discontinua-tions, extended supply chains,

strengthened regulation and shifts in the sour-cing of active pharmaceutical

ingredients from China, are all contributing to increasing stresses within the

supply chain, increasing risks to supply. The risks associated with the supply

of counterfeit medicines are also increasing. The Department of Health

(supported by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency), the

PMSG, NHS CMU and the trade associations all work together to minimise these

risks.

Product coding

The establishment of

the Dictionary of Medicines and Devices, its acceptance and increasing

application mean that the NHS has, for the first time ever, access to

nationally recognised coding and product descriptions. Linked to bar coding

(GS1), which is currently underutilised within hospital pharmacy, this will

create unprecedented opportunities to improve hospital pharmacy supply management.

Local arrangements

The majority of

pharmacy departments now use information technology systems for ordering, goods

receipt and invoice processing. These systems are configured so that the audit

requirement for segregation of these tasks between different staff members is

delivered. Procedures must be consistent with the trust’s standing financial

instructions. Manual systems are occasionally used but these will be phased out

and will not be covered here.

Ordering

Items which need to

be ordered will be identified by the computer system or by pharmacy staff.

Computer systems maintain live stock levels and, as these fall to the reorder

level, the item is flagged for reorder. The reorder level is either fixed or

can be calculated by the system based on an algorithm of average daily usage,

time it takes to be delivered (lead time) and a preset safety factor.

Infrequently used items may be flagged so that they are only placed on order by

authorised staff.

The system will

allocate these items to a preferred supplier that will be one of the following:

· the contract holder

· the manufacturer

offering an NHS price

· a short-line store

· a wholesaler

These lists of items

will be reviewed and amended by an authorised mem-ber of staff and orders

generated. The supplier may be charged if the lead time is not appropriate for

patient needs or the preferred supplier is out of stock. The orders will be

sent to the supplier by one of the following methods:

· verbally by phone

this method is useful if the item is urgent or patient-specific. If used

routinely, verbal ordering is labour-intensive and subject to transcription

errors

· faxing: this reduces

transcription errors but requires re-entering of data by the supplier and is

dependent on the quality of the faxed copy

· electronic data

interchange: this is exchange of electronic order data. It is the objective of

all NHS ordering. The accuracy is dependent on the upkeep of product codes and

so on, but it has the potential for rapid, accurate transfer, with minimal time

commitment for staff. Examples include use of the Pharmacy Messenger system and

Medecator

· post: this route is

now rarely used due to time delay and cost.

Goods receipt

On receipt, goods

will be checked visually for damage and expiry date. They will then be checked

against the delivery note and against either a hard copy or computer copy of an

order. The aim is to ensure that quantities and products are correct and that

there are no obvious defects. Any discrepancies will be notified to the

supplier immediately. Many trusts collect data on errors and timeliness of

deliveries since supplier performance is a key consideration at contract

adjudication. Once checks are complete, items will be entered into the computer

system and stock levels updated.

Batch number details

are recorded in some trusts, although the benefit of this is reduced by the

inability to track batches to the end-user. There is a requirement to do this

with blood products and medicines used in reproductive health services.

When controlled drugs

are ordered and receipted, the requirements of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations

must be followed. Records of receipt are made in a register and the balance of

stock received updated (see Chapter 5 for a more detailed discussion of

controlled drugs)

Invoicing

Practice varies

between trusts: this function is carried out by pharmacy staff in approximately

80% of trusts and by finance staff in the remainder. Wherever it is carried

out, the system requires input of invoice data into the computer system and checking

of price invoiced against price expected on the original order. Most trusts

require exact matching of contract line prices and agreed tolerances with

non-contract prices but use last purchase price on the orders.

Historically,

invoices have been received in hard copy with details manually entered into the

computer system. The receipt of electronic invoice files and subsequent

matching of items is developing rapidly and is used to some extent in 20% of

trusts. These systems automatically process items with complete matching of

data and allow trust staff to focus on price or delivery discrepancies.

Acceptance of

invoice details will update the unit cost of the item(s) on the computer system

and also authorise payment to the supplier.