Antipsychotic Drugs

| Home | | Pharmacology |Chapter: Essential pharmacology : Drugs Used In Mental Illness: Antipsychotic And Antimanic Drugs

These are drugs having a salutary therapeutic effect in psychoses.

ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS

(Neuroleptics)

These are drugs having

a salutary therapeutic effect in psychoses.

Classification

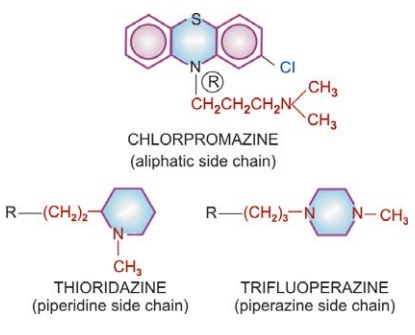

1. Phenothiazines

Aliphatic side chain: Chlorpromazine,Triflupromazine

Piperidine side chain: Thioridazine

Piperazine side chain: Trifluoperazine,

Fluphenazine

2. Butyrophenones

Haloperidol

Trifluperidol

Penfluridol

3.Thioxanthenes

Flupenthixol

4.Other heterocyclics

Pimozide

Loxapine

5.Atypical antipsychotics

Clozapine

Risperidone

Olanzapine

Quetiapine

Aripiprazole

Ziprasidone

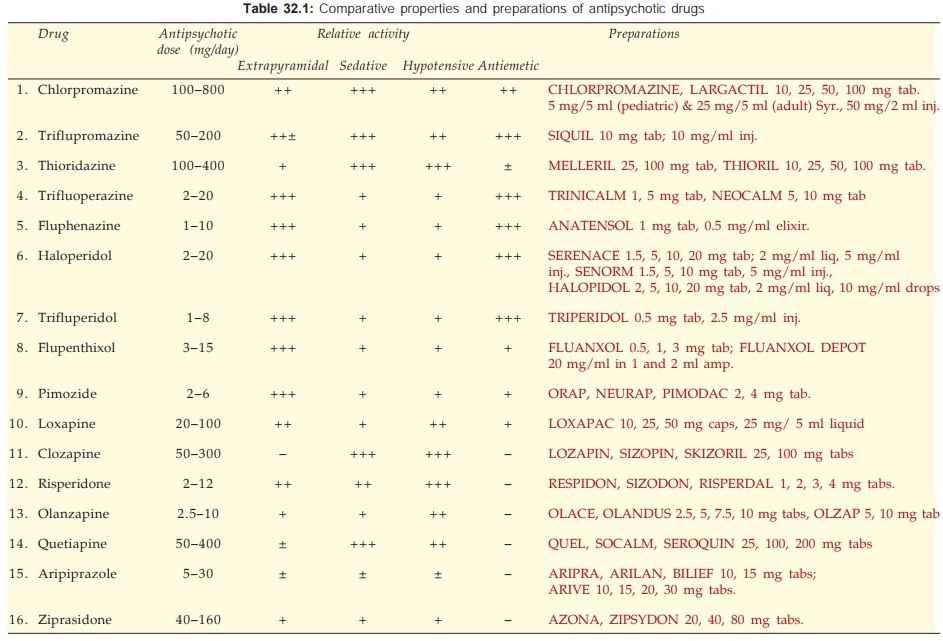

Many more drugs have been marketed in other countries but do not

deserve special mention. Pharmacology of chlorpromazine (CPZ) is described as

prototype; others only as they differ from it. Their comparative features are presented

in Table 32.1.

Pharmacological Actions

1. CNS

Effects differ in normal

and psychotic individuals.

In normal individuals CPZ produces

indifference to surroundings,

paucity of thought, psychomotor slowing, emotional quietening, reduction in

initiative and tendency to go off to sleep from which the subject is easily arousable.

Spontaneous movements are minimized but slurring of speech, ataxia or motor

incoordination does not occur. This has been referred to as the ‘neuroleptic

syndrome’ and is quite different from the sedative action of barbiturates and

other similar drugs. The effects are appreciated as ‘neutral’ or ‘unpleasant’

by most normal individuals.

In a psychotic CPZ reduces irrational

behaviour, agitation and aggressiveness and controls psychotic symptomatology.

Disturbed thought and behaviour are gradually normalized, anxiety is relieved.

Hyperactivity, hallucinations and delusions are suppressed.

All phenothiazines,

thioxanthenes and butyrophenones have the same antipsychotic efficacy, but

potency differs in terms of equieffective doses. The aliphatic and piperidine side

chain phenothiazines (CPZ, triflupromazine, thioridazine) have low potency,

produce more sedation and cause greater potentiation of hypnotics, opioids,

etc. The sedative effect is produced promptly, while antipsychotic effect takes

weeks to develop. Moreover, tolerance develops to the sedative but not to the

antipsychotic effect. Thus, the two appear to be independent actions.

Performance and

intelligence are relatively unaffected, but vigilance is impaired. Extrapyramidal

motor disturbances (see adverse

effects) are intimately linked to the antipsychotic effect, but are more

prominent in the high potency compounds and least in thioridazine, clozapine

and other atypical antipsychotics. A predominance of lower frequency waves

occurs in EEG and arousal response is dampened. However, no consistent effect

on sleep architecture has been noted. The disturbed sleep pattern in a

psychotic is normalized.

Chlorpromazine lowers

seizure threshold and can precipitate fits in untreated epileptics. The piperazine

side chain compounds have a lower propensity for this action. Temperature

control is knocked off at relatively higher doses rendering the individual

poikilothermic—body temperature falls if surroundings are cold. The medullary

respiratory and other vital centres are not affected, except at very high

doses. It is very difficult to produce coma with these drugs. Neuroleptics,

except thioridazine, have potent antiemetic action exerted through the CTZ. However,

they are ineffective in motion sickness.

In animals, neuroleptics

selectively inhibit ‘conditioned avoidance response’ (CAR) without

blocking the unconditioned response to a noxious stimulus. This action has

shown good correlation with the antipsychotic potency of different compounds, though

it may be based on a different facet of action. In animals, a state of rigidity

and immobility (catalepsy) is produced which resembles the bradykinesia seen

clinically.

Mechanism Of Action

All antipsychotics

(except clozapinelike

atypical) have potent dopamine D2 receptor blocking action; antipsychotic

potency has shown good correlation with their capacity to bind to D2 receptor.

Phenothiazines and thioxanthenes also block D1, D3 and D4 receptors, but there

is no correlation with antipsychotic potency. Blockade of dopaminergic

projections to the temporal and prefrontal areas constituting the ‘limbic

system’ and in mesocortical areas is probably responsible for the antipsychotic

action. This along with the observation that drugs which increase DA activity

(amphetamines, levodopa, bromocriptine) induce or exacerbate schizophrenia has

given rise to the ‘Dopamine theory of

Schizophrenia’ envisaging DA overactivity in limbic area to be responsible

for the condition. As an adaptive change to blockade of D2 receptors, the firing

of DA neurones and DA turnover increases initially. However, over a period of

time this subsides and gives way to diminished activity, especially in the

basal ganglia—corresponds to emergence of parkinsonian side effect. Tolerance

to DA turnover enhancing effect of antipsychotics is not prominent in the

limbic area—may account for the continued antipsychotic effect.

The above model fails

to explain the antipsychotic activity of clozapine and other atypical

antipsychotics which have weak D2 blocking action. However, they have

significant 5HT2 and α1 blocking action, and

some are relatively selective for D4 receptors. Thus, antipsychotic property

may depend on a specific profile of action of the drugs on several

neurotransmitter receptors. Recent positron emission tomography (PET) studies of

D2 and other receptor

occupancy in brains of

antipsychotic treated patients have strengthened this concept.

Dopaminergic blockade

in the basal ganglia appears to cause the extrapyramidal symptoms, while that

in CTZ is responsible for antiemetic action.

2. ANS

Neuroleptics have

varying degrees of α adrenergic blocking

activity which may be graded as:

CPZ = triflupromazine

> thioridazine > clozapine > fluphenazine > haloperidol >

trifluoperazine > pimozide, i.e. more potent compounds have lesser α blocking activity.

Anticholinergic

property of neuroleptics is weak and may be graded as:

thioridazine > CPZ

> triflupromazine > trifluoperazine = haloperidol.

The phenothiazines

have weak H1antihistaminic and anti5HT actions as well.

3. Local Anaesthetic

Chlorpromazine is as potent a local anaesthetic as procaine.

However, it is not used for this purpose because of its irritant action. Others

have weaker membrane stabilizing action.

4. CVS

Neuroleptics produce

hypotension (primarily postural) by a central as well as peripheral action on

sympathetic tone. The hypotensive action is more marked after parenteral

administration and roughly parallels the α adrenergic blocking

potency. Hypotension is not prominent in psychotic patients, but is accentuated

by hypovolemia. Partial tolerance develops after chronic use. Reflex

tachycardia accompanies hypotension.

High doses of CPZ

directly depress the heart and produce ECG changes (QT prolongation and

suppression of T wave). CPZ exerts some antiarrhythmic action, probably due to

membrane stabilization. Arrhythmia may occur in overdose, especially with thioridazine.

5. Skeletal

Muscle

Neuroleptics have no effect on muscle fibres or neuromuscular transmission. They reduce certain types of spasticity: the site of action being in the basal ganglia or medulla oblongata. Spinal reflexes are not affected.

6. Endocrine

Neuroleptics

consistently increase prolactin release by blocking the inhibitory action of DA

on pituitary lactotropes. This may result in galactorrhoea and gynaecomastia.

They reduce gonadotropin secretion, but amenorrhoea and

infertility occur only occasionally. ACTH release in response to stress is

diminished—corticosteroid levels fail to increase under such circumstances.

Release of GH is also reduced but this is not sufficient to cause growth

retardation in children or to be beneficial in acromegaly. Decreased release of

ADH may result in an increase in urine volume. A direct action on kidney

tubules may add to it, but Na+ excretion is not affected.

Tolerance And Dependence

Tolerance to the sedative and hypotensive actions develops

within days or weeks, but maintenance doses in most psychotics remain fairly

unchanged over years, despite increased DA turnover in the brain. The

antipsychotic, extrapyramidal and other actions based on DA antagonism do not

display tolerance.

Neuroleptics are hedonically (pleasurably) bland drugs. Physical

dependence is probably absent, though some manifestations on discontinuation

have been considered withdrawal phenomena. No drug seeking behaviour is

exhibited.

Pharmacokinetics

Oral absorption of CPZ is somewhat unpredictable and

bioavailability is low. More consistent effects are produced after i.m. or i.v.

administration. It is highly bound to plasma as well as tissue proteins—brain

concentration is higher than plasma concentration. Volume of distribution,

therefore, is large (20 L/kg). It is metabolized in liver, mainly by CYP 2D6

into a number of metabolites.

The acute effects of a

single dose generally last for 6–8 hours. The elimination t½ is variable, but

mostly is in the range of 18–30 hours. The drug cumulates on chronic

administration and it is possible to give the total maintenance dose once a

day. Some metabolites are probably active. The intensity of antipsychotic

action is poorly correlated with plasma concentration. Nevertheless,

therapeutic effect may be seen at 30–200 ng/ ml. The metabolites are excreted

in urine and bile for months after discontinuing the drug.

The broad features of

pharmacokinetics of other neuroleptics are similar.

Distinctive Features Of Neuroleptics

Antipsychotic drugs differ in potency and in their propensity to produce different effects. This is summarized in a comparative manner in Table 32.1.

Triflupromazine

An aliphatic side chain phenothiazine, somewhat more potent than CPZ.

Used mainly as antiemetic; it frequently produces acute muscle dystonias in

children; especially when injected.

Thioridazine

A low potency

phenothiazine having marked central

anticholinergic action. Incidence of extrapyramidal side effects is very low.

Cardiac arrhythmias and interference with male sexual function are more common.

Risk of eye damage limits long-term use.

Trifluoperazine,

Fluphenazine

These are high potency piperazine side chain phenothiazines.

They have minimum autonomic actions. Hypotension, sedation and lowering of

seizure threshold are not significant. They are less likely to cause jaundice

and hypersensitivity reactions. However, extrapyramidal side effects are

marked.

Fluphenazine decanoate

can be given as a depot i.m. injection every 2–4 weeks.

ANATENSOL DECANOATE,

PROLINATE 25 mg/ml inj.

Haloperidol

It is a potent antipsychotic with pharmacological

profile resembling that of piperazine substituted phenothiazines. It produces few

autonomic effects, is less epileptogenic, does not cause weight gain, jaundice

is rare. It is the preferred drug for acute schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease

and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Elimination t½ averages 24 hours.

Trifluperidol

It is similar to but slightly more potent than

haloperidol.

Penfluridol

An exceptionally long

acting neuroleptic,

recommended for chronic schizophrenia, affective withdrawal and social maladjustment.

Dose: 20–60 mg (max 120 mg)

once weekly; SEMAP, FLUMAP, PENFLUR 20 mg tab.

Flupenthixol

It is less sedating

than CPZ; indicated in

schizophrenia and other psychoses, particularly in withdrawn and apathetic

patients, but not in those with psychomotor agitation or mania. Infrequently

used now.

Pimozide

It is a specific DA antagonist with little α adrenergic or

cholinergic blocking activity. Because of long duration of action (several

days; elimination t½ 48–60 hours) after a single oral dose, it is considered

good for maintenance therapy but not when psychomotor agitation is prominent.

Incidence of dystonic reactions is low, but it tends to prolong myocardial APD

and carries risk of arrhythmias. It has been particularly used in Gilles de la

Tourett’s syndrome and ticks.

Loxapine

A dibenzoxazepine

having CPZ like DA blocking and

antipsychotic activity. The actions are quick and short lasting (t½ 8 hr). No

clear cut advantage over other antipsychotics has emerged.

Atypical Antipsychotics

These are newer

(second generation) antipsychotics that have weak D2 blocking but potent 5HT2

antagonistic activity. Extrapyramidal side effects are minimal, and they may

improve the impaired cognitive function in psychotics.

Clozapine

An atypical

antipsychotic; pharmacologically distinct from others in that it has only weak

D2 blocking action, produces few/no extrapyramidal symptoms; tardive dyskinesia

is rare and prolactin level does not rise. It suppresses both positive and

negative symptoms of schizophrenia and many patients refractory to typical

neuroleptics respond. The differing pharmacological profile may be due to its

relative selectivity for D4 receptors (which are sparse in basal ganglia) and

additional 5HT2 as well as α blockade. It is quite sedating, moderately

potent anticholinergic, but paradoxically induces hypersalivation. Significant

H1 blocking property is present.

Clozapine is

metabolized primarily by CYP3A4 with an average t½ of 12 hours. Its major

limitation is higher incidence of agranulocytosis (0.8%) and other blood

dyscrasias: weekly monitoring of leucocyte count is required. High dose can

induce seizures even in nonepileptics. Other side effects are sedation,

unstable BP, tachycardia, urinary incontinence, weight gain and precipitation

of diabetes. Few cases of myocarditis have been reported which start like flu

but may progress to death.

Clozapine is used as a

reserve drug in resistant schizophrenia.

Risperidone

Another compound whose antipsychotic activity has been ascribed to a

combination of D2 + 5HT2 receptor blockade. In addition it has high

affinity for α1, α2 and H1

receptors: blockade of these may contribute to efficacy as well as side effects

like postural hypotension. However, BP can rise if it is used with selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Risperidone is more potent D2 blocker than clozapine;

extrapyramidal side effects are less only at low doses (<6 mg/day).

Prolactin levels rise during risperidone therapy, but it is less epileptogenic

than clozapine, though frequently causes agitation. Caution has been issued

about increased risk of stroke in the elderly.

Olanzapine

This atypical antipsychotic; resembles clozapine in

blocking multiple monoaminergic (D2, 5HT2, α1, α2) as well as

muscarinic and H1 receptors. Both positive and negative symptoms of

schizophrenia appear to be benefited. A broader spectrum of efficacy covering

schizoaffective disorders has been demonstrated, and it is approved for use in

mania. Monotherapy with olanzapine may be as effective as a combination of

lithium/valproate + benzodiazepines.

Olanzapine is a potent antimuscarinic, produces dry mouth and

constipation. Weaker D2 blockade results in few extrapyramidal side effects and

little rise in prolactin levels, but is more epileptogenic than high potency

phenothiazines; causes weight gain and carries a higher risk of worsening

diabetes. Incidence of stroke may be increased in the elderly. Agranulocytosis

has not been reported with olanzapine. Olanzapine is metabolized by CYP1A2 and

glucuronyl transferase. The t½ is 24–30 hours.

Quetiapine

This new short-acting (t½ 6 hours) atypical

antipsychotic requires twice daily dosing. It

blocks 5HT1A, 5HT2, D2, α1, α2 and H1

receptors in the brain, but D2 blocking activity is low:

extrapyramidal and hyper-prolactinaemic side effects are minimal. However, it

is quite sedating (sleepiness is a common side effect), and postural

hypotension can occur, especially during dose titration. Urinary retention/

incontinence are reported in few patients. Weight gain and rise in blood sugar

are infrequent. Quetiapine has not been found to benefit negative symptoms of

schizophrenia, but can be used in mania/bipolar disorder. It is metabolized

mainly by CYP3A4; can interact with macrolides, antifungals, anticonvulsants,

etc.

Aripiprazole

This atypical

antipsychotic is unique in being a

partial agonist at D2 and 5HT1A receptor, but antagonist at 5HT2

receptor. It is minimally sedating, may even cause insomnia. Extrapyramidal

side effects, hyperprolactinaemia, hypotension and QT prolongation are not

significant. Little tendency to weight gain and rise in blood sugar has been

noted. Frequent side effects are nausea, dyspepsia, constipation and lightheadedness.

Aripiprazole is quite long-acting

(t½ ~ 3 days); dose adjustments should be done after 2 weeks treatment. It is

metabolized by CYP3A4 as well as CYP2D6; dose needs to be halved in patients

receiving ketoconazole or quinidine, and doubled in those taking carbamazepine.

Aripiprazole is indicated in schizophrenia as well as mania and bipolar

illness.

Ziprasidone

It is the latest

atypical antipsychotic with combined D2 + 5HT2A/2C + H1 +

α1 blocking activity.

Antagonistic action at 5HT1D + agonistic activity at 5HT1A

receptors along with moderately potent inhibition of 5HT and NA reuptake

indicates some anxiolytic and antidepressant property as well. Like other

atypical antipsychotics, ziprasidone has low propensity to cause extrapyramidal

side effects or hyperprolactinaemia. It is mildly sedating, causes modest

hypotension and little weight gain or blood sugar elevation. Nausea and

vomiting are the common side effects. More importantly, a doserelated

prolongation of QT interval occurs. It has the potential to induce serious

cardiac arrhythmias, especially in the presence of predisposing factors/drugs.

The t½ of ziprasidone

is ~8 hours; needs twice daily dosing. In comparative trials, its efficacy in

schizophrenia has been rated equivalent to haloperidol. It is also indicated in

mania.

Adverse Effects

Neuroleptics are very

safe drugs in single or infrequent doses: deaths from overdose are almost

unknown. However, side effects are common.

Based On Pharmacological Actions (Dose Related)

CNS Drowsiness, lethargy, mental confusion: more

with low potency agents; tolerance develops; increased appetite and weight gain

(not with haloperidol); aggravation of seizures in epileptics; even nonepileptics

may develop seizures with high doses of some antipsychotics like clozapine and

olanzapine. However, potent phenothiazines risperidone, quetiapine,

aripiprazole and ziprasidone have little effect on seizure threshold.

CVS Postural hypotension, palpitation,

inhibition of ejaculation (especially with thioridazine) are due to α adrenergic blockade;

more common with low potency phenothiazines. QT prolongation and cardiac

arrhythmias are a risk of overdose with thioridazine, pimozide and ziprasidone.

Anticholinergic Dry mouth, blurring of vision, constipation, urinary hesitancy in

elderly males (thioridazine has the highest propensity); absent in high potency

agents. Some like clozapine induce hypersalivation despite anticholinergic

property, probably due to central action.

Endocrine Hyperprolactinemia

(due to D2 blockade) is common

with typical neuroleptics and risperidone. This can lower Gn levels, but

amenorrhoea, infertility, galactorrhoea and gynaecomastia occur infrequently

after prolonged treatment. The atypical antipsychotics do not appreciably raise

prolactin levels.

Extrapyramidal

Disturbances These are the major dose

limiting side effects; more prominent with high potency drugs like

fluphenazine, haloperidol, pimozide, etc., least with thioridazine, clozapine,

and all other atypical antipsychotics, except high doses of risperidone. These

are of following types.

Parkinsonism with typical

manifestations— rigidity, tremor,

hypokinesia, mask like facies, shuffling gait; appears between 1–4 weeks of

therapy and persists unless dose is reduced. If that is not possible, one of

the anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs may be given concurrently. Though

quite effective, routine combination of the anticholinergic from the start of

therapy in all cases is not justified. Levodopa is not effective.

A rare form of extrapyramidal side effect is perioral tremors

‘rabbit syndrome’ that generally occurs after a few years of therapy. It often

responds to central anticholinergic drugs.

Acute Muscular

Dystonias Bizarre muscle spasms, mostly

involving linguofacial muscles —grimacing, tongue thrusting, torticollis,

locked jaw; occurs within a few hours of a single dose or at the most in the

first week of therapy. It is more common in children below 10 years and in

girls, particularly after parenteral administration; overall incidence is 2%. It

lasts for one to few hours and then resolves spontaneously. One of the central

anticholinergics, promethazine or hydroxyzine injected i.m. clears the reaction

within 10–15 min.

Akathisia Restlessness, feeling

of discomfort, apparent agitation manifested as a compelling desire to move

about, but without anxiety, is seen in some patients between 1–8 weeks of

therapy: upto 20% incidence. It may be mistaken for exacerbation of psychosis.

Mechanism of this complication is not understood; no specific antidote is

available. A central anticholinergic may reduce the intensity in some cases;

propranolol is more effective, but most cases require reduction of dose or an

alternative antipsychotic. Addition of diazepam may help.

Malignant Neuroleptic

Syndrome It occurs rarely with high doses

of potent agents; the patient develops marked rigidity, immobility, tremor,

fever, semi-consciousness, fluctuating BP and heart rate; myoglobin may be

present in blood—lasts 5–10 days after drug withdrawal and may be fatal. The

neuroleptic must be stopped promptly and symptomatic treatment given. Though,

antidopaminergic action of the neuroleptic may be involved in the causation of

this syndrome; anticholinergics are of no help. Intravenous dantrolene may

benefit. Bromocriptine in large doses has been found useful.

Tardive Dyskinesia It occurs late in

therapy, sometimes even after

withdrawal of the neuroleptic: manifests as purposeless involuntary facial and

limb movements like constant chewing, pouting, puffing of cheeks, lip licking,

choreoathetoid movements. It is more common in elderly women; probably a

manifestation of progressive neuronal degeneration along with supersensitivity

to DA. It is accentuated by anticholinergics and temporarily suppressed by high

doses of the neuroleptic (this should not be tried except in exceptional

circumstances). An incidence of 10–20% has been reported after long term treatment;

uncommon with clozapine and all other atypical antipsychotics. The dyskinesia

may subside months or years after withdrawal of therapy or may be lifelong.

There is no satisfactory solution of the problem.

Miscellaneous

Weight gain often occurs with long term

antipsychotic therapy; blood sugar and lipids may tend to rise. Risk of

worsening of diabetes is more with clozapine and olanzapine, but minimal with

haloperidol, aripiprazole and ziprasidone. Blue

pigmentation of exposed skin, corneal

and lenticular opacities, retinal

degeneration (more with thioridazine) occur rarely after long-term use of high doses of phenothiazines.

Hypersensitivity Reactions These are not dose related.

Cholestatic

Jaundice with portal

infiltration; 2–4% incidence; occurs

between 2–4 weeks of starting therapy. It calls for withdrawal of the

drug—resolves slowly. More common with low potency phenothiazines; rare with

haloperidol.

Skin rashes,

urticaria, contact dermatitis, photosensitivity (more with CPZ).

Agranulocytosis is rare; more common with clozapine.

Myocarditis Few cases have occurred with clozapine.

Interactions

·

Neuroleptics potentiate all CNS depressants

—hypnotics, anxiolytics, alcohol, opioids, antihistaminics and analgesics.

Overdose symptoms may occur.

·

Neuroleptics block the actions of levodopa and

direct DA agonists in parkinsonism.

·

Antihypertensive action of clonidine and methyldopa

is reduced, probably due to central α2 adrenergic blockade.

·

Phenothiazines and others are poor enzyme

inducers—no significant pharmacokinetic interactions. Enzyme inducers

(barbiturates, anticonvulsants) can reduce blood levels of neuroleptics.

Uses

1. Psychoses

Schizophrenia The antipsychotics are

used primarily in functional psychoses: have indefinable but definite

therapeutic effect in all forms: produce a wide range of symptom relief. They

control positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thought,

restlessness, insomnia, anxiety, fighting, aggression) better than negative symptoms

(apathy, loss of insight and volition, affective flattening, poverty of speech,

social withdrawal). However, they tend to restore cognitive, affective and

motor disturbances and help upto 90% patients to lead a near normal life in the

society. But, some patients do not respond, and virtually none responds completely.

They are only symptomatic treatment, do not remove the cause of illness; long-term

(even lifelong) treatment may be required. They cause little improvement in

judgement, memory and orientation. Patients with recent onset of illness and

acute exacerbations respond better.

Choice of drug is

largely empirical, guided by the presenting symptoms (it is the target symptoms

which respond rather than the illness as a whole), associated features and mood

state, and on the type of side effect that is more acceptable in a particular

patient. Individual patients differ in their response to different antipsychotics;

there is no way to predict which patient will respond better to which drug. The

following may help drug selection:

·

Agitated, combative and violent—CPZ,

thioridazine, haloperidol, quetiapine.

·

Withdrawn and apathetic—trifluoperazine, fluphenazine,

aripiprazole, ziprasidone.

·

Patient with mainly negative symptoms and

resistant cases—clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, ziprasidone

(evidence of their higher efficacy is not firm).

·

Patient with mood elevation, hypomania—

haloperidol, fluphenazine, olanzapine.

·

If extrapyramidal side effects must be avoided

—thioridazine, clozapine or any other atypical antipsychotic.

·

Elderly patients who are more prone to sedation,

mental confusion and hypotension—a high potency phenothiazine, haloperidol,

aripiprazole or ziprasidone.

Currently, the newer atypical antipsychotics are being more

commonly prescribed. Though, there is no convincing evidence of higher

efficacy, they produce fewer side effects and neurological complications. They

are preferable for long-term use in chronic schizophrenia due to lower risk of

tardive dyskinesia. Of the standard neuroleptics, the high potency agents are

preferable over the older low potency ones.

Mania Antipsychotics are required

for rapid control; CPZ or haloperidol

may be given i.m.— act in 1–3 days; lithium or valproate may be started

simultaneously or after the acute phase. After 1–3 weeks when lithium has taken

effect, the neuroleptic may be withdrawn gradually. Recently, oral therapy with

one of the atypical antipsychotics olanzapine/risperidone/aripiprazole/quetiapine

is being preferred for cases not requiring urgent control.

Organic Brain Syndromes Neuroleptics are not very effective. May be used on a short-term

basis—one of the potent drugs is preferred to avoid mental confusion,

hypotension and precipitation of seizures.

The dose of

antipsychotic drugs should be individualized by titration with the symptoms and

kept at minimum. In chronic schizophrenia maximal therapeutic effect is seen

after 2–4 months therapy. However, injected neuroleptics control aggressive symptoms

of acute schizophrenia over hours or a few days. Combination of 2 or more

neuroleptics is not advantageous. However, a patient on maintenance therapy with

a non-sedative drug may be given additional CPZ or haloperidol by i.m.

injection to control exacerbations or violent behaviour.

In a depressed

psychotic, a tricyclic antidepressant may be combined. Benzodiazepines may be

added for brief periods in the beginning.

Low dose maintenance or

intermittent regimens of antipsychotics have been tried in relapsing cases.

Depot injections, e.g. fluphenazine/ haloperidol decanoate given at 2–4 week

intervals are preferable in many cases.

2. Anxiety

Neuroleptics relieve

anxiety but should not be used for

simple anxiety because of autonomic and extrapyramidal side effects:

benzodiazepines are preferable. However, those not responding or having a

psychotic basis for anxiety may be treated with a neuroleptic.

3. As Antiemetic

Neuroleptics are

potent antiemetics—control a

wide range of drug and disease induced vomiting at doses much lower than those

needed in psychosis. However, they should not be given unless the cause of

vomiting has been identified. They are effective in morning sickness but should

not be used for this purpose. They are ineffective in motion sickness: probably

because dopaminergic pathway through the CTZ is not involved in this condition.

4. Other Uses

To

potentiate hypnotics, analgesics and anaesthetics Justified only in

anaesthetic practice.

a)

Intractable hiccough may respond to parenteral

CPZ.

b) Tetanus CPZ is a secondary

drug to achieve skeletal muscle

relaxation.

c)

Alcoholic

hallucinosis, Huntington’s disease and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome are rare indications.

Related Topics